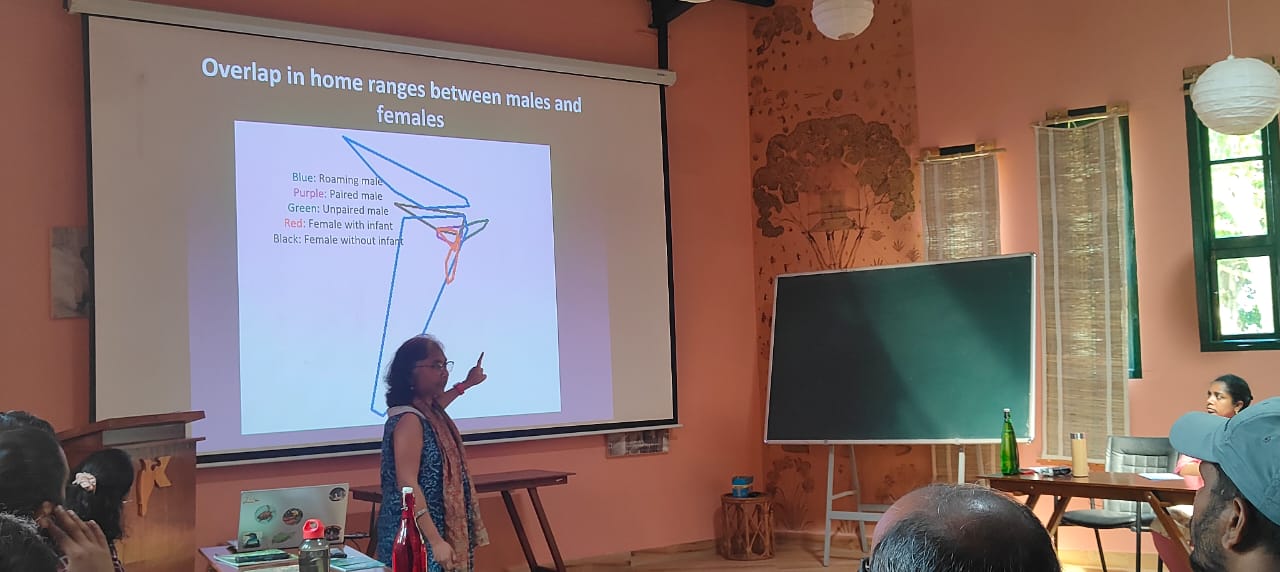

We often look for wildlife in forests, oceans, grasslands and all pristine habitats tucked away from villages, towns and cities. Seldom does one realise that there is wildlife in our backyard, sharing spaces and resources with us. Once we start to observe different life forms that cohabit with us, we also start to realise that we influence their behaviour as well. Though this interaction can be positive, most often, it’s negative. While wildlife is constantly adapting to changes in their surroundings, we need to understand what triggers these changes and why and how to peacefully coexist with them.

Nestled in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, the semi-urban town of Kotagiri has seen rapid expansion in the last couple of years, changing the way land is used and resources are shared. In order to understand how these changes have affected wildlife and triggered increased human-wildlife interactions, our team, which includes community volunteers, are monitoring sites such as waterholes, wetlands, streams, and garbage dumps. In addition, transact walks and roadkill transacts are being carried out to get an understanding of the wildlife presence as well as identify important road-crossing areas. This has helped us in setting up signages in these areas.

While the above methodologies are adopted to capture the diversity of wildlife sharing spaces with humans, we are also trying to understand the behaviour patterns of one of the most frequently sighted mammals in and around Kotagiri—the gaurs. Although not perceived as a serious threat, gaurs can be unpredictable under different circumstances. Hence, we are trying to understand these animals through recording their focal behaviour, feeding behaviour and herd composition. Keystone staff Chandrasekar, a Kotagiri resident shares more details in the recording below about the kind of wildlife monitoring activities carried out in Kotagiri.

Analysis from the research carried out has helped us in creating and restoring important water sources and refugee areas that are used by wildlife to prevent them from straying closer to human habitations. Furthermore, we were also able to identify important animal-crossing junctions and put up signages there. Implementing these strategies wouldn’t have been possible without active participation from various communities, the forest department and private landholders.

By Nayantara Lakshman