By Snehlata Nath – with inputs from Rajendran, Justin, Shiny and Anita

“Trees are poems that the earth writes upon the sky.” — Kahlil Gibran

This article is an ode to a tree that was a constant presence in our journeys through Mudumalai Tiger Reserve. It was a message from Rajendran on 2nd May this year…”Today, due to heavy rain and wind, the bee-catching tree completely fell down, damaging hundreds of bees”.

Rajendran is from the Irula community from Chokkanahalli, and our senior team member. He is an avid beekeeper, raises nurseries of forest plants and is a keen observer of nature’s ways.

The tree he mentions is a Bombax Ceiba (Malabar silk cotton; Kattu Elavam Panji) standing tall by the roadside between Theppakadu and Thorapally in the Mudumalai Tiger Reserve.

Photo: 25th April, 2025

People always drove on this road with care and alertness to see wildlife – elephants, sambar deer, chital, wild boar and the often-sighted peacock. However, we at Keystone had our eyes towards canopies to locate bee colonies on big trees found along the Moyar.

Mudumalai Bee Survey, 2019

We have focused on Apis dorsata, the Giant Rock Bee, since we began our work over three decades ago. Bees are an excellent indicator of the environment – its biodiversity and ecological cycles. A migratory bee species, colonies of Apis dorsata come to the hills in mid-February/March and stay through the spring and summer. Flowering in the forest is at its peak during this time – Naval (Syzygium cuminii), Mango (Mangifera indica), Palash (Butea monosperma), Vaagai(Albizia lebbeck), Konnai (Cassia fistula), Urugul maram (Chloroxylon swietenia), Dalbergia lanceolaria etc.

Every year the bees will come back from the plains to settle in the Nilgiris cliffs and trees. With abundant nectar and pollen, their colonies grow and when the young ones are ready to fly and the monsoon sets in, the colonies leave the hills by July.

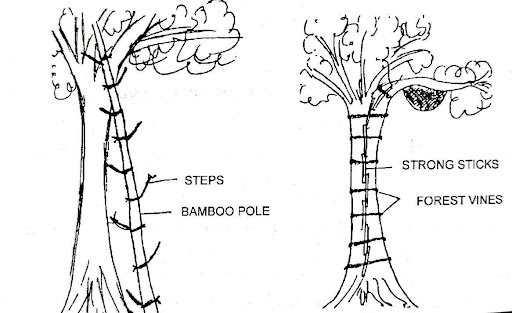

In the Nilgiris, the Adivasi communities have a special relationship with bees and our work over the years has highlighted the cultural, social and economic dimensions. In the Mudumalai area, the community of Kattunaickens are excellent honey gatherers using bamboo scaffolding or single bamboo ladders to climb trees and harvest honey on moonlit nights.

After the forest was declared a wildlife sanctuary and later a tiger reserve, authorities restricted people’s access. As a result, the traditional practice of honey collection is fading, weakening the deep bond between people and nature. For many, honey has been vital—for sustenance, rituals, and income. A largely alienated community, now mainly work as wage laborer’s in farms and tea estates.

Several surveys and studies done by us have mapped rock cliffs and big trees which are the habitat for Apis dorsata and this tree was one of them. One felt like a midget in front of this giant tree, making counting colonies difficult, especially when the road traffic is high. Measuring approximately 70 feet in height and 15 feet girth, DBH estimates the tree to be many hundred years old. Its branches were home to hundreds of colonies. Besides honeybees, it also supports various bird and insect species due to its large canopy and seasonal flowers.

Between January to March, the tree blooms with large red flowers which are highly attractive to pollinators, especially bees and many birds. Fruit setting starts in March/April and the tree develops large, pod-like fruits that contain silky cotton-like fibres and seeds.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bombax_ceiba_with_Cracking_Fruits.JPG

Over the years, we observed Apis dorsata colonies

- 2007: ~120 colonies

- 2015: ~70 colonies

- 2019: 8 colonies with more than 200 deserted combs

- 2025 (April): ~50 colonies

We see a decline in the colony population trend over time, possibly due to environmental pressures, habitat disturbance and climatic changes.

We have observed big colonies on very thin branches on this tree. The bees are the best judge of which branch could take the weight of their family. The weight increases over the season as pollen and nectar is sored, egg laying increases and young bees grow.

Roadside Bombax Ceiba, Mudumalai Bee Survey, 2019

Our team, once passing under the tree in the evening at dusk, were blessed with the phenomenon of ‘yellow rain’. The bees of several colonies leave their combs en-masse and defecate together, resulting in a yellow powdery rain which is often observed under bee trees. This is mistaken for pollen, which is not shared at all by them but packed in cells diligently. Bees are known to do this to reduce colony temperatures and body weight, as larvae are sensitive to heat and may get deformed or die. Having been covered with yellow rain several times before, our team just laughed and talked at length about social behavior and organization in bee colonies. It was admirable and disciplined – so unlike our own Keystone Foundation!

The ecological importance of this old tree in the forest is immense – it is the standing testimony to a primary forest, witnessing ecological changes over three centuries! They have specific functions in hydrology and soil, mycelium regimes, micro environment as well as support to many other species in the forest. Many Bombax ceiba trees are centuries old, like the ~300-year-old trees observed. These aging trees are naturally falling or dying due to structural weakness, fungal decay, or wind damage. Replacement with younger trees is slow, and natural regeneration is being hampered by forest disturbances, like invasives.

Fallen Bombax tree in Mudumalai – R. Rajendran

When a tree dies in a tropical forest, decay and decomposition happen quickly. It is aided by a host of species – fungi, weevils, bugs, earthworms and birds. The soil has added nutrients and new dormant foliage starts to grow. Being on the roadside, the falling of this tree has not caused a classic tree fall gap in the canopy, but it has created a huge gap for bee habitat. At Keystone, we will miss this tree immensely and ending with a quote in its honour……

“Ancient trees are precious. There is little else on Earth that plays host to such a rich community of life within a single living organism.” — Sir David Attenborough

References and Further Readings:

Thomas, Sumin & Varghese, Anita & Roy, Pratim & Bradbear, Nicola & Potts, Simon & Davidar, Priya. (2009). Characteristics of trees used as nest sites by Apis dorsata (Hymenoptera, Apidae) in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, India. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 25. 10.1017/S026646740900621X.

Keystone Foundation Internal Report: A decadal assessment of honey bee nesting sites in forests of Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, India; 2020; Anita Varghese, Asish Mangalaserri, Jenner J.

An interesting story about yellow rain discovery: https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/magazine/the-mystery-of-yellow-rain/

MARDAN, M., KEVAN, P. Honeybees and ‘yellow rain’. Nature 341, 191 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1038/341191a0