November 3, 2023

By Harshavardhinin Angappan

Technical Coordinator, Restoration Practitioner – Biodiversity Conservation

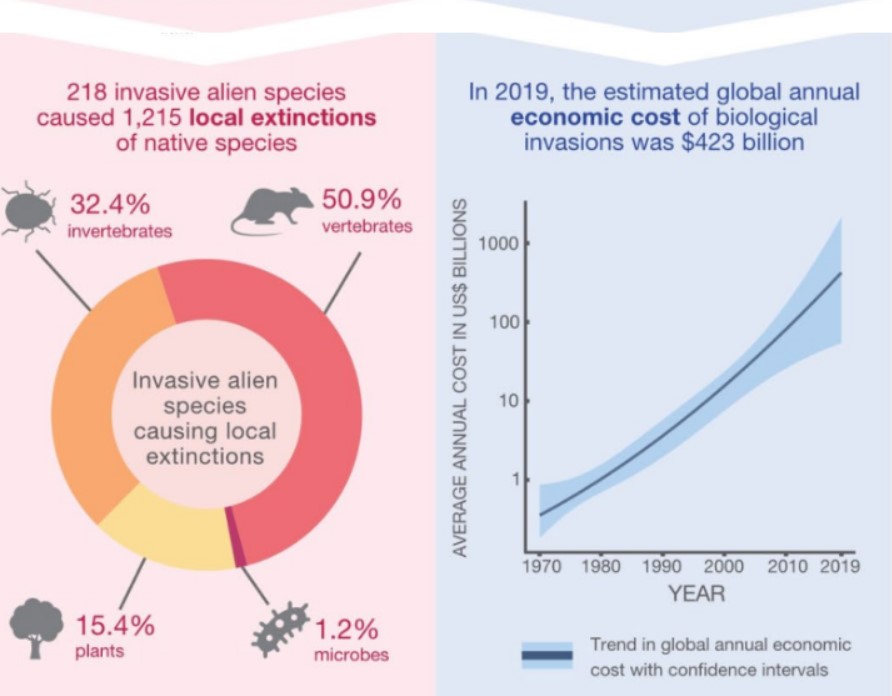

The 2023 report by Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) that assessed invasive alien species found them to be one of the main drivers of change in nature worldwide alongside land and sea use change, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change and pollution. These drivers also have different levels of importance in facilitating biological invasions across different biomes making invasive alien species a major threat to natural resources and quality of life. The report reveals that 218 invasive alien species have caused the local extinction of 1,215 native species globally and estimates the global annual economic cost of biological invasion at US$423 billion in 2019.

The spread of invasive alien plants has been a major focus in ecological restoration efforts since its impacts have been increasing rapidly and are predicted to continue rising in the future. The Nilgiris has been severely affected by invasive alien species, like most hilly districts, since British colonisers introduced Mediterranean and European plants to mimic the landscape of Europe (Narasimhan et al, 2010). The impact of these species on the nature of the Nilgiris, its contribution to people and good quality of life of people in the Nilgiris are yet to be studied.

One of Keystone’s activities since our beginnings in 1993 was the promotion of native species nurseries that focussed on raising, propagating and planting native plants. In the past decade, we have increased our focus on stakeholder engagement and integrated governance in restoring degraded lands that are severely impacted by spread of invasive species. Several wetlands, common lands, stream banks and forest boundaries are impacted by unregulated waste dumping, encroachments, improper disposal of untreated sewage and soil erosion, to name some of the countless threats. We conduct the rehabilitation of these lands by raising awareness among the public on behaviour in ecologically sensitive areas, the scientific removal of invasives, and finally, planting appropriate native species. The practice of ecological restoration requires a high level of ecological knowledge, especially from local communities (Gann et al., 2019).

Four methods that emerged from field trials to remove and control the growth of invasive species in ecological restoration sites are uprooting invasive species; applying organic weedicides that are formulated by local communities; using a weed-control mat used in horticulture; and controlled fire as practised traditionally. These methods are described in detail below.

- Uprooting of invasive plant species: is done manually using tools like knives, garden hoes, and pickaxes. This method is used most specifically for removing woody stemmed invasive species like, Lantana camara, Acacia mearnsii, Cestrum aurantiacum and large shrubs like Solanum mauritianum. These plants are first cut before uprooting and preferably the cutting is done before seeds are produced, i.e before fruiting season, to prevent the seeds from spreading and contributing to the seed bank. After uprooting, the woody branches are taken as firewood for local household level use.

Our observations show that with this method, resprouting is suppressed even though regeneration of the invasive plants occurs from seeds present in the soil. These regenerated seedlings are then regularly removed manually. Advantage of this method is that, if in a place where both native and invasive plant species are found, since the removal is done manually one can be selective to remove only the invasive plants. This method is heavily dependent on wage labour. Sometimes access to sites which are interior becomes difficult after a few months since the path itself becomes overgrown with undergrowth.

- Applying organic weedicides prepared locally: organic weedicide, which is made from cow urine, powder of Terminalia chebula fruits, neem oil and soap, which is used here as an emulsifier, is sprayed on grasses and herbaceous weeds like Parthenium hysterophorus. This weedicide is formulated by the State Agricultural Extension Management Institute (STAMIN) and the knowledge about it is widely shared with local farming communities who are interested in organic agriculture. The weedicide is ideally sprayed in the morning of a sunny day to be effective. The sun and the salts in the weedicide dries the weed within three days, eventually wilting and killing the plant. The dried plant can then be pulled out of the ground and removed or left there as a mulch. This weedicide can be sprayed once every month and the effect lasts for the whole month. The advantage of using this method is that the time consumed for application is less when compared to manually uprooting and needs less manpower. Since the weedicide is organic, it does not affect the soil organisms like earthworm and holds the soil integrity. But it can be applied only when there is good sun as the rain washes off the weedicide from the plants making it ineffective. In this method, local native seedlings may also be destroyed.

- Using a weed control mat: it is laid out in smaller restoration sites like stream banks and common areas in villages. These mats suppress the growth of weeds by blocking sunlight. The native plants are then planted by cutting out holes on these mats. This method has not been efficient when the terrain is hilly as the mats are easily washed away with the rain. Since the weed mats may also suppress other native species, this is not a method we use widely.

- Controlled fire as practised traditionally: The Irula community use controlled firing as a practice to clear land for farming. They use fire in the summer season during April and May when the conditions are dry. The invasive plant species are initially cut, dried and then gathered into heaps within the plots before firing under supervision. The ash from burning is spread in the farmland as it helps in the growth of the crop especially millets. After this treatment, the regeneration of invasives is seen only after three months, if the rains are less, as the heat generated during the burning process penetrates through the soil for a few inches and damages the seeds in the seed bank. The community is very confident of using fire though again this is not a preferred method since many soil dwelling organisms, ground egg laying animals, amphibians, reptiles are impacted when the fires are set. In special cases when the thickets of invasive plants have been impenetrable then fire has been used so that the site can be accessed.

In conclusion we want to document in more detail the methods employed to control invasive plants since this is the most important first step to preparing a degraded piece of land for ecological restoration. The four methods explained above are the current ones being used by the team at Keystone Foundation. We are in the process of documenting the methods, efforts taken, frequency of control measures and efficiency measured as resurgence of invasive species. In our experience all four methods have their own advantages and disadvantages. Before scaling up to use the methods in large scale restoration projects, experimental pilot projects should be carried out to understand the effects and effectiveness of each method against different invasive plant species under different climatic conditions. Also one should balance out ecological, economical and social benefits in using each method while selecting the best method to treat the invasive plant species in a particular site.

A Note on the Nilgiris

The Nilgiris, a mountainous Indian district, is situated in the northwestern part of the state of Tamil Nadu and surrounded by other states of India viz. Karnataka in the north and Kerala in the west. This district in South India is part of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve (NBR) which was the first Biosphere Reserve of the country declared in 1986 under UNESCO’s Man and Biosphere programme. The district falls within the Western Ghats range of NBR which is a global biodiversity hotspot that displays a convergence of Afro-tropical and Indo-Malayan biotic zones. Spread over an elevation range of 1000 m to 2600 m, the district has varied climatic conditions along with peculiar topographic features that create a diverse combination of temperature and moisture regimes reflecting on the diversity of vegetation communities and species found therein. Varying from seasonal rainforests in the low hills to Southern Montane Wet Temperate Forests (locally called ‘Shola forests’) and montane grasslands in the higher elevations, this district holds within its boundary all important forest types of Southern India which is unique in the whole of India (Sekar, 2004). Anthropogenic stressors over the past few years like forest resources exploitation, encroachment, development projects, change in land use practices, and spread of invasive species have contributed to degradation of the forests (Sekar, 2004).

References:

Gann GD, McDonald T, Walder B, Aronson J, Nelson CR, Jonson J, Hallett JG, Eisenberg C, Guariguata MR, Liu J, Hua F, Echeverría C, Gonzales E, Shaw N, Decleer K, Dixon KW (2019) International principles and standards for the practice of ecological restoration. Second edition: November 2019. Society for Ecological Restoration, Washington, D.C. 20005 U.S.A.

IPBES (2023). Summary for Policymakers of the Thematic Assessment Report on Invasive Alien Species and their Control of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Roy, H. E., Pauchard, A., Stoett, P., Renard Truong, T., Bacher, S., Galil, B. S., Hulme, P. E., Ikeda, T., Sankaran, K. V., McGeoch, M. A., Meyerson, L. A., Nuñez, M. A., Ordonez, A., Rahlao, S. J., Schwindt, E., Seebens, H., Sheppard, A. W., and Vandvik, V. (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7430692

Narasimhan, D., Arisdason, W., Irwin, S. J., & Gnanasekaran, G. (2010). Invasive alien plant species of Tamil Nadu. In National Seminar on Invasive Alien Species (pp. 29-38).

Sekar, T. (2004). Forest History of The Nilgiris. Tamilnadu Forest Department. 01/03/2004