September 16, 2023

By Bhavya George

Programme Coordinator, Climate Change

Keystone’s team members and projects are part of countless national and global networks that foster collaboration and support for action, and offer rich platforms for knowledge exchange. One such network that we treasure is Climate Uncertainties, of which Keystone has been part for a year. Other partners include the South Asia Institute of Advanced Studies in Nepal, Royal Thimphu College in Bhutan, and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, with Sweden leading the programme.

After a year of a purely digital existence, we geared for 10 days of the first in-person network meeting in the Nilgiris, at our Keystone campus. As a host organisation, Jyotsna and I began planning and preparation months ago and looked forward to connecting offline.

Hailing from different mountain landscapes, our global network landed here on September 6. It was especially exciting to meet Professor Adam Pain from the network. He is an old friend of Keystone who worked with us more than a decade back on the Darwin Project on Biodiversity and Livelihoods. For Professor Pain, this meeting in the Nilgiris had some recollections from his earlier visit and work.

We engaged in insightful conversations on commonalities and differences. A large takeaway from these conversations was our shared interest in local experiences, be it food, art and craft, music, textiles, landscape.

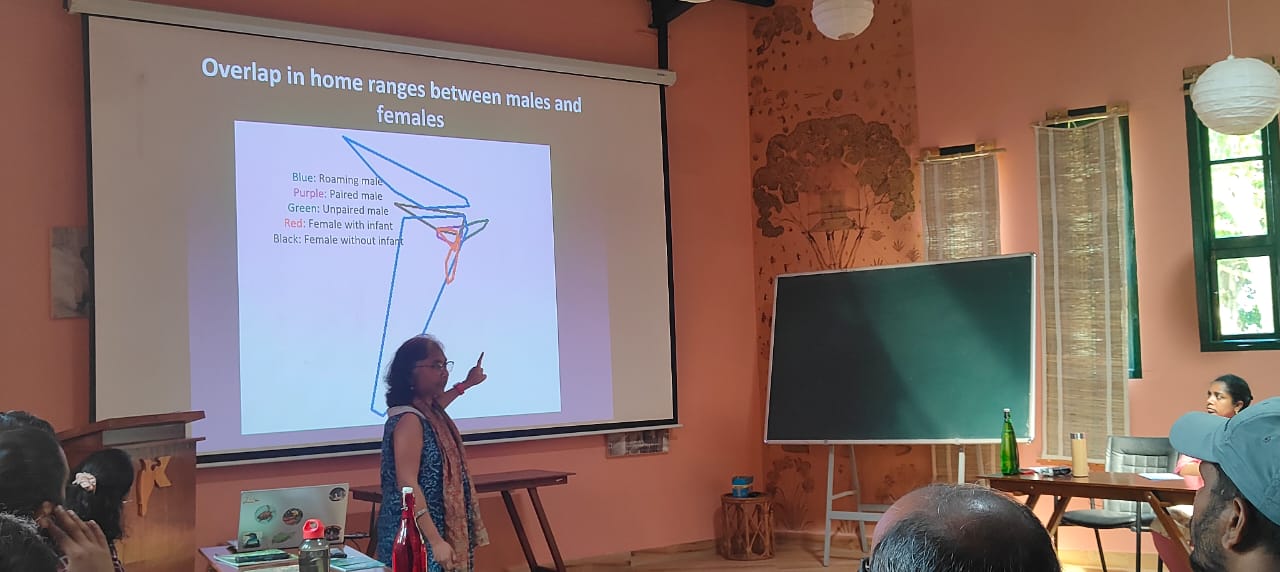

Our ten days were a mix of field visits, stakeholder meets, discussions and deliberations on the project and methodologies. It helped us as a network to gain a fresh perspective on the importance of this collaboration and to understand the lived experience and sources of uncertainty in mountain livelihoods. As the title ‘Climate Uncertainties’ implies, the interest of this collaborative work, as mentioned in the proposal, is “to build understanding of the uncertainties that poor rural households face in South Asian Mountains and how they respond to them. The collaboration aims to shift thinking away from a risk to an uncertainty framing of the hazards of mountain lives, paying attention to the time preference behaviour of poor people and generate new research capacities, proposals, and deliberative policy approaches to respond to this”.

Through this network, I learned about how uncertainties and time preference behaviour are linked to climate change and can be used as a framework in looking at mountain specificities, namely fragility, marginality, remoteness, and diversity. ‘Uncertainties’ refers not only to natural resources, but also includes the action and impact of markets, institutions, and governance.

Using these discussions, we were able to apply the lens of uncertainties to our work with communities and connect stories from the field to this framework. Field visits and interactions with the field staff and community resource persons strengthened the understanding.

We visited Banagudi, Aracode, Bikapathy Mund and Sigur. I think that the magic of joint field visits lies in how they help us identify our similarities and differences. There are times that during our share outs I was able to travel to Nepal, Bhutan and Sweden in my imagination. Another thing I learnt during the field visits was the discipline of debriefing–though it would be late in the evening, we would still make it a point to debrief after our visits. It helped to summarise the takeaways of the day and head home with some food for thought.

When we initially planned our meeting, 10 days seemed like a long time. In actuality, we did not realise how quickly the days went by. These days made me understand that one of the significant benefits of a network is meeting new people and becoming more aware of different perspectives. This meeting helped us in the systematic formulation of plans for the future. We bid goodbye with an exchange of cultural items from our regions and look forward now to our second network meeting in the coming year in Bhutan.