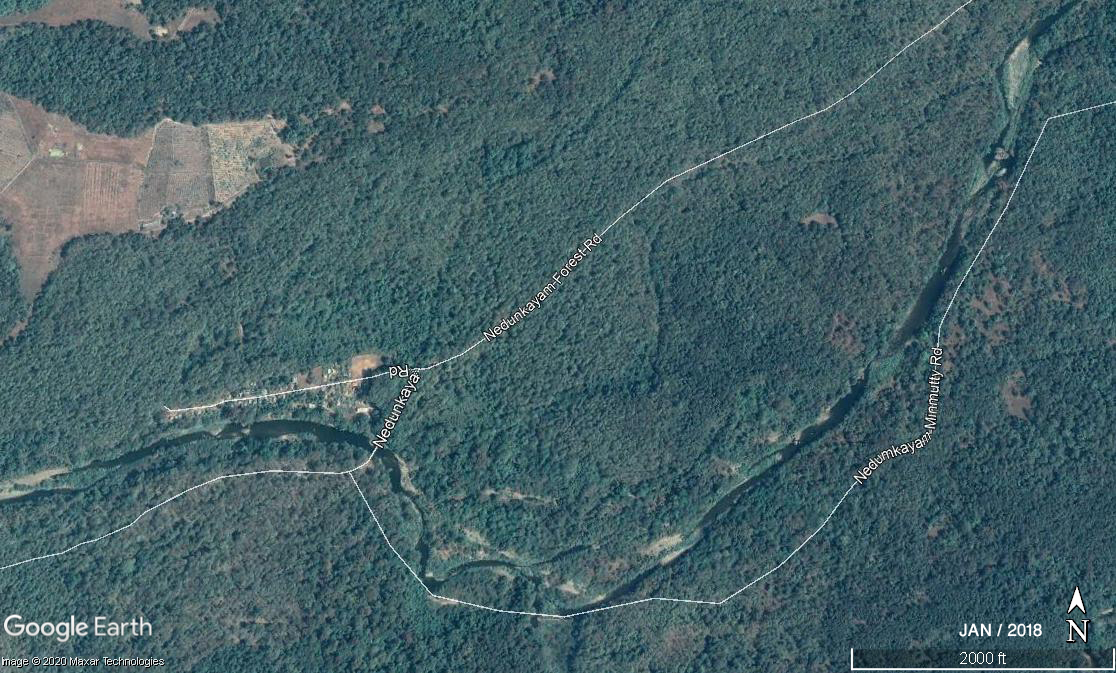

In 2018 and 2019, Kerala experienced extreme rainfall which resulted in floods and landslides. Apart from loss of lives, there was significant amount of infrastructural damage caused in Nilambur. Overflowing rivers washed away some Adivasi villages displacing many families. With these memories fresh in their mind, the people await another dreaded monsoon.

Satellite image showing Karimpuzha of Jan/2018 and Feb/2020. The debris and the marks of overflown river can be seen.

The Nilambur region is considered a biodiversity hotspot and accorded a great degree of protection. The New Amarambalam Reserve Forests lying within Nilambur division forms a part of the core zone of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. Being the fourth largest river in Kerala, the Chaliyar River and its watershed spread over Nilambur. Moreover, this is the largest undammed river in Kerala, hosting several endemic species and endangered species making it a key biodiversity area. The important tributaries of the river system are- the Chalipuzha, the Cherupuzha, the Punnapuzha, the Pandiyar, the Karimpuzha, the Vadapurampuzha, the Iruvanjipuzha and the Iruthilpuzha.

History tells us that most civilizations originate in the river banks as rivers support their water requirements, livelihood, transportation, etc. In India, there is a spiritual connect with these water bodies where some rivers are worshiped. But what is most striking about river systems are the ecological services they have to offer. It is then no coincidence that the Adivasi people always choose settlements near rivers. In Nilambur, most of the adivasi villages are situated in the banks of tributaries of river Chaliyar.

Nilambur is home to indigenous communities who are considered distinctive in their livelihood and social set up. The Cholanaicken are hunter gatherers who maintain a forest dependent lifestyle. They are considered to be the only indigenous community in mainland India that still resides in caves. Other major forest dependent indigenous communities of the region include the Pathinaicken, Kattunaicken, Paniyas and Ernadans. However, in recent times, wage labor has come to be ranked as the major livelihood. Although, communities living close to the river and its tributaries still depend on fishing as a seasonal livelihood.

The floods of 2018 and 2019 caused massive devastation from which the affected are yet to recover. The torrential rains led to landslides and floods, resulting in social, economic and ecological disruption. The floods were so intense that it changed to course of the river in some areas in Nilambur. The loss was immense, where communities- majority belonging to Adivasi groups- faced huge capital losses, leaving some displaced and consequently resettled. The ecological damages and consequences are yet to be assessed.

In such times of unpredictability, it is the need of the hour to pay attention to the changes happening around us and adapt accordingly. Likewise, the hunter gatherers who live along the river banks used to move to the upper slopes of the hills during the monsoons. They don’t need calendar to decide this. With their traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), they might able to see and foresee more than us. In these years of extreme rainfall they have been relying on their traditional wisdom to adapt, taking them to higher grounds to stay safe.

To ensure that these traditional knowledge systems are not lost, Keystone Foundation is helping communities document these ecological wisdoms which are used as indicators to gauge extreme climatic events. To further understand the ecological damages and consequences of the floods, the team is facilitating ecological monitoring and documentation of changes in the river and forest ecosystems with the communities in Nilambur. Among these activities, there was also studies done on bees and NTFP’s in the valley as well as engaging in conservation education activities in the region.

By Asish Mangalasseri